History

Long Branch survived the Civil War, the Reconstruction era, the Great Depression, and two world wars. Named a Virginia Historic Landmark in 1968 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, Long Branch is significant for its relation to national, regional, and local historical narratives.

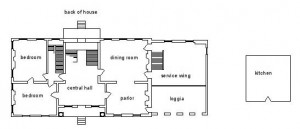

In 1788, Robert Carter Burwell, a descendant of Robert “King” Carter, inherited the land sitting along a stream known as Long Branch in Clarke County, Virginia. Utilizing the labor of enslaved workers, Burwell started a wheat plantation on the land he inherited. About twenty years later, around 1810, he began to construct a mansion on the site. Burwell, along with the help of a local builder-architect, designed and constructed the house following the classical principles suggested to him by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, architect of the U.S. Capitol, in a letter dated July 21, 1811. Latrobe recommended that Burwell include a servant’s staircase and that the dining room and chamber be oriented to the south side of the house.

While it is unclear if Burwell was able to incorporate all of Latrobe’s recommendations into the final design of Long Branch, he did include the servant’s staircase that can still be seen today. Burwell did not have much time to enjoy his new home, for he fell fatally ill in the filthy camps around Norfolk, Virginia while serving in the military during the War of 1812.

Following Burwell’s death, the property passed into the ownership of his sister, Sarah, and her husband Philip Nelson. While Burwell had died in 1813, it appears that the Nelson’s did not move in until around 1820. Details on their early tenancy are scarce, but by the 1830s sources indicate they operated the house as a school for girls and maintained the grounds as a wheat plantation. Philip’s son Thomas then opened a boy’s school at Rosney, the plantation home immediately north of Long Branch. It is likely that Philip was responsible for the addition of an open-air loggia to the house – the eastern brick addition.

Philip’s ownership of Long Branch was mainly characterized by difficult economic conditions, including the Panic of 1825 and 1837. While Philip, like Robert Burwell before him, utilized enslaved laborers and servants to run his plantation, he still struggled to make Long Branch extremely profitable, and by the early 1840s, he was apparently forced to sell to his nephew, Hugh Mortimer Nelson. Philip and Sarah would live the rest of their lives back at Rosney, the home that they had lived in before moving to Long Branch.

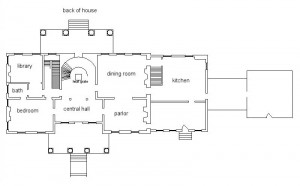

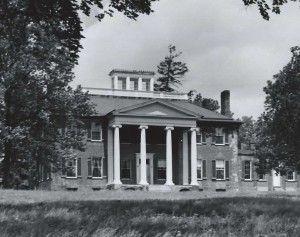

In 1842, Hugh M. Nelson paid $32,000 for Long Branch, and by the late 1840s, he oversaw a series of updates and changes to the home and plantation. Hugh and his wife Adelaide enclosed the loggia making a larger “kitchen” space and oversaw a comprehensive Greek revival renovation which included construction of the spiral staircase, interior trim and doors based on the designs of architect Minard Lafever, new windows and window casings, and both north and south columned porticos.

Hugh, one of Clarke County’s delegates to the Virginia secession convention, was a pro-Union delegate as were many residents of the Valley. All of Hugh’s speeches from the debates survive, including an impassioned speech concerning the impact of a war on his native region:

I come from the banks of the sparkling Shenandoah, “Daughter of the stars,” as its name imports. I live within a day's march of the Thermopylae of Virginia. That valley, now beautiful and peaceful “as the Vale of Tempe, may be a very Bochim – a place of weeping.” Those green fields, where now “lowing herds wind slowly o'er the lea,” may become fields of blood. Can you blame me, then, if I wish to try all peaceful means, consistent with Virginia honor, of obtaining our rights, before I try the last resort?

Despite Hugh’s position during the debates, following Virginia’s decision to secede in the spring of 1861, he sided with his native state and commanded the 6th Virginia Cavalry. Hugh rose through the ranks and ultimately gained a position as Aide-de-Camp on Confederate General Richard Ewell’s staff. Hugh was severely wounded during the Seven Days’ Campaign of the Civil War, June 25 – July 1, 1862, and ultimately died of infection a little over a month later in August.

Following Hugh M. Nelson’s death, the Nelson family struggled to maintain ownership of the property and years of legal wrangling ensued. Adelaide Nelson and her son, Hugh Nelson Jr., struggled to pay back Hugh Nelson Sr.’s debts, while at the same time maintaining the wheat plantation without the help of enslaved laborers in a struggling southern economy.

The Nelson family ultimately held on to the house until the 1950s – but the financial deprivations caused by the destruction of the pre-war economy forced the family to live a much different lifestyle. Unlike their antebellum predecessors, the Nelsons of the late 19th century, primarily Hugh Nelson Jr. and his wife Sallie Page Nelson, were unable to redecorate the house and acquire much new furniture. The result was that house and its interior furnishings remained remarkably unchanged from the 1860s until 1951.

When Sallie Page Nelson passed away in 1951, the Nelson heirs to the house decided to sell Long Branch. The Nelson family’s 144-year ownership of Long Branch officially ended in 1957 when Abram and Dorothy Hewitt purchased the home for $125,000.

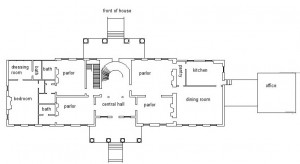

Abram Hewitt was a corporate financial advisor who served for the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor to the CIA) during World War II. His wife, Dorothy Hewitt, was originally from New Orleans and served as a ferry pilot in England during World War II. Together, Abram and Dorothy raised four sons while living at Long Branch. They made several structural changes to the interior of the house and also rebuilt the summer kitchen structure, which Abram used as his office. While raising their family at Long Branch, the Hewitts also raised beef and grew corn, alfalfa, and other crops. Due to financial difficulties in the late 1970s, Abram and Dorothy reluctantly sold Long Branch in 1978.

After the Hewitt’s ownership, the house passed through several subsequent owners and speculators, ultimately landing on the courthouse steps in 1986 at an auction where Harry Z. Isaacs, a Baltimore textile executive, purchased the estate. Isaacs oversaw a large-scale rehabilitation of the house and furnished it to be his home. Before his death in 1990, Isaacs created and endowed the Harry Z. Isaacs Foundation “to hold, preserve, maintain and operate Long Branch Farm… for charitable purposes.”

Today, Long Branch serves the community’s families as an ideal Virginia wedding reception venue, and our gardens are the backdrop of exquisite Virginia functions. The daily operation of Long Branch Farm also includes a horse retirement facility where our trusted equine friends live out their remaining years.